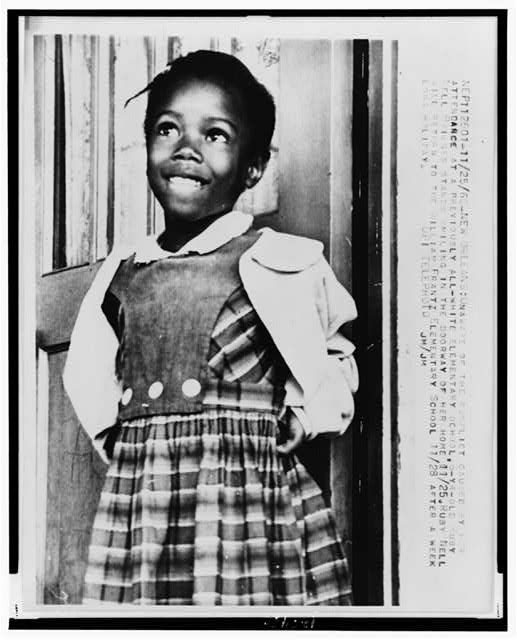

Ruby Bridges was born on September 8, 1954, in Tylertown, Mississippi. In 1960, when she was 6 years old, her parents responded to a call from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and volunteered her to participate in the integration of the New Orleans School system. She is known as the first African-American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South. Born in Mississippi, when she was four her parents, Abon and Lucille Bridges, moved to New Orleans for the hope of a better life in a bigger city. Her father got a job as a gas station attendant and her mother took night jobs to help support their growing family. Soon Ruby had two younger brothers and a younger sister.

Ruby Bridges was born on September 8, 1954, in Tylertown, Mississippi. In 1960, when she was 6 years old, her parents responded to a call from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and volunteered her to participate in the integration of the New Orleans School system. She is known as the first African-American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South. Born in Mississippi, when she was four her parents, Abon and Lucille Bridges, moved to New Orleans for the hope of a better life in a bigger city. Her father got a job as a gas station attendant and her mother took night jobs to help support their growing family. Soon Ruby had two younger brothers and a younger sister.

The fact that she was born the same year the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision desegregated the schools is a notable coincidence to her early journey into civil rights activism. When young Ruby was in kindergarten, she was one of many African-American students in New Orleans who were chosen to take a test determining whether or not she could attend a white school. It is said the test was written to be especially difficult so that students would have a hard time passing. The idea was if all the African-American children failed the test, New Orleans schools might be able to stay segregated for a while longer. She lived a mere five blocks from an all-white school, but attended kindergarten several miles away in an all-black segregated school

Her father was averse to his daughter taking the test, believing that if she passed and was allowed to go to the white school, there would be trouble. Her mother Lucille, however, pressed the issue, believing that Ruby would get a better education at a white school. She was eventually able to convince Ruby’s father to let her take the test.

In 1960, Ruby Bridges’ parents were informed by officials from the NAACP that she was one of only six other African-American students to pass the test. Ruby would be the only African-American student to attend the William Frantz School, near her home. When the first day of school rolled around in September, Ruby was still at her old school. All through the summer and early fall, the Louisiana state legislature had found ways to fight the federal court order and slow the integration process. After exhausting all stalling tactics, the legislature had to relent, and the designated schools were to be integrated in November. Fearing there might be some civil disturbances, the federal district court judge requested the U.S. government send federal marshals to New Orleans to protect the children.

In 1960, Ruby Bridges’ parents were informed by officials from the NAACP that she was one of only six other African-American students to pass the test. Ruby would be the only African-American student to attend the William Frantz School, near her home. When the first day of school rolled around in September, Ruby was still at her old school. All through the summer and early fall, the Louisiana state legislature had found ways to fight the federal court order and slow the integration process. After exhausting all stalling tactics, the legislature had to relent, and the designated schools were to be integrated in November. Fearing there might be some civil disturbances, the federal district court judge requested the U.S. government send federal marshals to New Orleans to protect the children.

On the morning of November 14, 1960, federal marshals drove Ruby and her mother the five blocks to her new school. While in the car, one of the men explained that when they arrived at the school, two marshals would walk in front of Ruby and two would be behind her. The image of this small black girl being escorted to school by four large white men inspired Norman Rockwell to create the painting “The Problem We All Must Live With” which graced the cover of Look magazine in 1964.

When Ruby and the federal marshals arrived at the school, large crowds of people were gathered in front yelling and throwing objects. There were barricades set up, and policemen were everywhere. Ruby, in her innocence, first believed it was like a Mardi Gras celebration. When she entered the school under the protection of the federal marshals, she was immediately escorted to the principal’s office and spent the entire day there. The chaos outside, and the fact that nearly all the white parents at the school had kept their children home, meant classes weren’t going to be held.

Ruby Bridges’ first few weeks at Frantz School were not easy ones. Several times she was confronted with blatant racism in full view of her federal escorts. On her second day of school, a woman threatened to poison her. After this, the federal marshals allowed her to only eat food from home. On another day, she was “greeted” by a woman displaying a black doll in a wooden coffin. Ruby’s mother kept encouraging her to be strong and pray while entering the school, which Ruby discovered reduced the vehemence of the insults yelled at her and gave her courage. She spent her entire day, every day, in Mrs. Henry’s classroom, not allowed to go to the cafeteria or out to recess to be with other students in the school. When she had to go to the restroom, the federal marshals walked her down the hall. Several years later, federal marshal Charles Burks, one of her escorts, commented with some pride that Ruby showed a lot of courage. She never cried or whimpered. “She just marched along like a little soldier.”

Near the end of the first year, things began to settle down. A few white children in Ruby’s grade returned to the school. Occasionally, Ruby got a chance to visit with them. By her own recollection many years later, Ruby was not that aware of the extent of the racism that erupted over her attending the school. But when another child rejected Ruby’s friendship because of her race, she began to slowly understand.

By Ruby’s second year at Frantz School it seemed everything had changed. Mrs. Henry’s contract wasn’t renewed, and so she and her husband returned to Boston. There were also no more federal marshals; Ruby walked to school every day by herself. There were other students in her second grade class, and the school began to see full enrollment again. No one talked about the past year. It seemed everyone wanted to put the experience behind them.

Ruby Bridges finished grade school, and graduated from the integrated Francis T. Nicholls High School in New Orleans. She then studied travel and tourism at the Kansas City business school and worked for American Express as a world travel agent. In 1984, Ruby married Malcolm Hall in New Orleans, and later became a full-time parent to their four sons.

Source: BIO